John Prine (73) was born on October 10, 1946 and raised in Maywood, Illinois. Prine was the son of William Mason Prine, a tool-and-die maker, and Verna Valentine (Hamm), a homemaker, both originally from Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. In summers, they would go back to visit family near Paradise, Kentucky. Prine started playing guitar at age 14, taught by his brother, David. He attended classes at Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music, and graduated from Proviso East High School in Maywood, Illinois.

John Prine (73) was born on October 10, 1946 and raised in Maywood, Illinois. Prine was the son of William Mason Prine, a tool-and-die maker, and Verna Valentine (Hamm), a homemaker, both originally from Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. In summers, they would go back to visit family near Paradise, Kentucky. Prine started playing guitar at age 14, taught by his brother, David. He attended classes at Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music, and graduated from Proviso East High School in Maywood, Illinois.

He was drafted into the United States Army during the Vietnam War, serving as a vehicle mechanic in West Germany, before becoming a U.S. Postal Service mailman for five years leading up to beginning his musical career in Chicago.

“I likened the mail route to being in a library without any books. You just had time to be quiet and think, and that’s where I would come up with a lot of songs,” Prine said later.

While Prine was delivering mail, he began to sing his songs (often first written in his head on the mail route) at open mic nights at the Fifth Peg on Armitage Avenue in Chicago. The bar was a gathering spot for nearby Old Town School of Folk Music teachers and students. Prine was initially a spectator, reluctant to perform, but eventually did so in response to a “You think you can do better?” comment made to him by another performer. After his first open mic, he was offered paying gigs. In 1970, Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert heard Prine by chance at the Fifth Peg and wrote his first printed review, “Singing Mailman Who Delivers A Powerful Message In A Few Words”

Roger Ebert Review:

Through no wisdom of my own but out of sheer blind luck, I walked into the Fifth Peg, a folk club on West Armitage, one night in 1970 and heard a mailman from Westchester singing. This was John Prine. He sang his own songs. That night I heard “Sam Stone,” one of the great songs of the century. And “Angel from Montgomery.” And others. I wasn’t the music critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, but I went to the office and wrote an article. And that, as fate decreed, was the first review Prine ever received.

While “digesting Reader’s Digest” in a dirty book store, John Prine tells us in one of his songs, a patriotic citizen came across one of those little American flag decals. He stuck it on his windshield and liked it so much he added flags from the gas station, the bank and the supermarket, until one day he blindly drove off the road and killed himself. St. Peter broke the news: “Your flag decal won’t get you into heaven anymore; It’s already overcrowded from your dirty little war.”

Lyrics like this are earning John Prine one of the hottest underground reputations in Chicago these days. He’s only been performing professionally since July, he sings at the out-of-the-way Fifth Peg, 858 W. Armitage, and country-folk singers aren’t exactly putting rock out of business. But Prine is good.

He appears on stage with such modesty he almost seems to be backing into the spotlight. He sings rather quietly, and his guitar work is good, but he doesn’t show off. He starts slow. But after a song or two, even the drunks in the room begin to listen to his lyrics. And then he has you.

He does a song called “The Great Society Conflict Veteran’s Blues,” for example, that says more about the last 20 years in America than any dozen adolescent acid-rock peace dirges. It’s about a guy named Sam Stone who fought in Korea and got some shrapnel in his knee. But the morphine eased the pain, and Sam Stone came home “with a Purple Heart and a monkey on his back.” That’s Sam Stone’s story, but the tragedy doesn’t end there. In the chorus, Prine reverses the point of view with an image of stunning power:

“There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm Where all the money goes…”

You hear lyrics like these, perfectly fitted to Priine’s quietly confident style and his ghost of a Kentucky accent, and you wonder how anyone could have so much empathy and still be looking forward to his 24th birthday on Saturday.

So you talk to him, and you find out that Prine has been carrying mail in Westchester since he got out of the Army three years ago. That he was born in Maywood, and that his parents come from Paradise, Ky. That his grandfather was a miner, a part-time preacher, and used to play guitar with Merle Travis and Ike Everly (the Everly brothers’ father). And that his brother Dave plays banjo, guitar and fiddle, and got John started on the guitar about 10 years ago.

Prine’s songs are all original, and he only sings his own. They’re nothing like the work of most young composers these days, who seem to specialize in narcissistic tributes to themselves. He’s closer to Hank Williams than to Roger Williams, closer to Dylan than to Ochs. “In my songs,” he says, “I try to look through someone else’s eyes, and I want to give the audience a feeling more than a message.”

That’s what happens in Prine’s “Old folks,” one of the most moving songs I’ve heard. It’s about an elderly retired couple sitting at home alone all day, looking out the screen door on the back porch, marking time until death. They lost a son in Korea: “Don’t know what for; guess it doesn’t matter anymore.” The chorus asks you, the next time you see a pair of “ancient empty eyes,” to say “hello in there…hello.”

Prine’s lyrics work with poetic economy to sketch a character in just a few words. In “Angel from Montgomery,” for example, he tells of a few minutes in the thoughts of a woman who is doing the housework and thinking of her husband: “How the hell can a person go to work in the morning, come back in the evening, and have nothing to say?”

Prine can be funny, too, and about half his songs are. He does one about getting up in the morning. A bowl of oatmeal tried to stare him down, and won. But “if you see me tonight with an illegal smile – It don’t cost very much, and it lasts a long while. – Won’t you please tell the Man I didn’t kill anyone – Just trying to have me some fun.

”There’s another insightful one, for example, called “The Great Compromise,” about a girl he once dated who was named America. One night at the drive-in movie, while he was going for popcorn, she jumped into a foreign sports car and he began to suspect his girl was no lady. “I could have beat up that fellow,” he reflects in his song, “but it was her that hopped into his car.”

Roger Ebert’s laudatory review set the stage for this remarkable singer/songwriter. Quirky fact aside: “Ebert was being paid to watch and write a review of a film; but as he tells it the film was so bad that he walked out on it half way through, and went looking for a beer to cut the taste of the popcorn. If the film had been any better, Prine’s career might have been entirely different or started a little later”.

Singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson heard Prine at Steve Goodman’s (City of New Orleans) insistence, and Kristofferson invited Prine to be his opening act. Prine released his eponymous debut album in 1971, featuring such songs as “Paradise”, “Sam Stone” and “Angel from Montgomery“, giving bittersweet tragic-comic snapshots of American society and also fed into the anti-war movement. The album has been hailed as one of the greatest albums of all time.

The acclaim Prine earned from his debut led to three more albums for Atlantic Records. Common Sense (1975) was his first to chart on the Billboard U.S. Top 100. He then recorded three albums with Asylum Records. In 1981, he co-founded Oh Boy Records, an independent label which released all of his music up until his death. His final album, 2018’s The Tree of Forgiveness, debuted at #5 on the Billboard 200, his highest ranking on the charts.

Indeed, Prine was a rare songwriter with a gift for both melodic and lyrical incisiveness. He didn’t need to pull any verbal sorcery to make you gasp and think “Did he just do that?” The magic was all in how profoundly and bluntly he observed the most mundane details of life and death, even for characters living on the fringe. His melancholic tales were economical and precise in their gut-punches.

Prine’s lyrics work with poetic economy to sketch a character in just a few words. In “Angel from Montgomery,” for example, he tells of a few minutes in the thoughts of a woman who is doing the housework and thinking of her husband: “How the hell can a person go to work in the morning, come back in the evening, and have nothing to say?”

Prine can be funny, too, and about half his songs are. He does one about getting up in the morning. A bowl of oatmeal tried to stare him down, and won. But “if you see me tonight with an illegal smile – It don’t cost very much, and it lasts a long while. – Won’t you please tell the Man I didn’t kill anyone – Just trying to have me some fun.”

At the time John Prine was all over the magazines, but he was nowhere on the radio. But without a radio hit, Prine remained a cult item. Actually, he remained a cult item for his entire career. But it’s funny, cult can supersede major success if you hang in there and do it right.

But after the debut, Prine’s notoriety, his “fame,” the attention he got, seemed to go in the wrong direction, you knew who he was, but most people did not. He had fans who purchased his records, but only fans purchased his records and went to see him live.

Eventually Prine switched labels from Atlantic to Asylum, he worked with his old cohort Steve Goodman, but “Bruised Orange” did not live up to its commercial expectations. It was everywhere in print, I purchased it, but after its initial launch, that’s the last you heard of it. Eventually, after three LPs with the definitive singer-songwriter label, Prine took off on his own, with his Oh Boy Records, partnering with his manager Al Bunetta and their buddy Dan Einstein. It worked. His fans, supporting the project, sent him enough money to cover the costs, in advance, of his next album. Prine continued writing and recording albums throughout the 1980s. His songs continued to be covered by other artists; the country supergroup The Highwaymen recorded “The 20th Century Is Almost Over”, written by Prine and Goodman. Steve Goodman died of leukemia in 1984 and Prine contributed four tracks to A Tribute to Steve Goodman, including a cover version of Goodman’s “My Old Man”.

“How the hell can a person go to work in the morning, And come home in the evening and have nothing to say”

Everybody knew “Angel From Montgomery.” It was never a single, never a radio hit. They knew John Prine had written “Angel From Montgomery.” And the great thing about famous songs is they carry their writers along. So when Bonnie Raitt entered the music scene full force with a number of Grammy Awards in the 1990s, the original recorded version from “Streetlights” was superseded by her live performances, if the song got any airplay, it ended up being the live take from her 1995 double album “Road Tested.”

And as a result of this, suddenly the winds were at John Prine’s back, he was a known quantity, his impact increased, his career rose, and it was all because of this one song.

Of course Prine had songs covered by other famous artists, some of them you could even call hits, but I’m not sure fans of David Allan Coe really cared who’d written his numbers. And it wasn’t only Bonnie Raitt. Over the years other people had covered “Angel From Montgomery,” and Raitt’s success lifted all boats, suddenly “Angel From Montgomery” was part of the American fabric. And this is strange. This is akin to Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land,” a song everybody knows that was not featured on the hit parade, but contains the essence of America more than the tracks that are.

Now “Angel From Montgomery” reaches you on the very first listen.

“If dreams were thunder, and lightning were desire

This old house would have burnt down a long time ago”

That kernel, that inner mounting flame, if it goes out, you die.

“Just give me one thing that I can hold on to

To believe in this living is just a hard way to go”

But you wake up one day and you discover this is your life, that you’re trapped, that your dreams didn’t come true, and you’re not only frustrated, you’re angry.

So then there’s someone like John Prine, telling your story. That’s what you resonate with, you’re looking for understanding, someone who gets you. And America discovered this singer/songwriter en masse.

In 1991, Prine released the Grammy-winning The Missing Years, his first collaboration with producer and Heartbreakers bassist Howie Epstein. The title song records Prine’s humorous take on what Jesus did in the unrecorded years between his childhood and ministry. In 1995, Lost Dogs and Mixed Blessings was released, another collaboration with Epstein. On this album is the long track “Lake Marie”, a partly spoken word song interweaving tales over decades centered on themes of “goodbye”. Bob Dylan later cited it as perhaps his favorite Prine song. Prine followed it up in 1999 with In Spite of Ourselves, which was unusual for him in that it contained only one original song (the title track); the rest were covers of classic country songs. All of the tracks are duets with well-known female country vocalists, including Lucinda Williams, Emmylou Harris, Patty Loveless, Dolores Keane, Trisha Yearwood, and Iris DeMent.

In 2001 Prine appeared in a supporting role in the Billy Bob Thornton movie Daddy & Them. “In Spite of Ourselves” is played during the end credits.

Prine recorded a version of Stephen Foster‘s “My Old Kentucky Home” in 2004 for the compilation album Beautiful Dreamer, which won the Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album.

In 2005, Prine released his first all-new offering since Lost Dogs and Mixed Blessings, the album Fair & Square, which tended toward a more laid-back, acoustic approach. The album contains songs such as “Safety Joe”, about a man who has never taken any risks in his life, and also “Some Humans Ain’t Human”, Prine’s protest piece on the album, which talks about the ugly side of human nature and includes a quick shot at President George W. Bush. Fair & Squarewon the 2005 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album.

On June 22, 2010, Oh Boy Records released a tribute album titled Broken Hearts & Dirty Windows: Songs of John Prine.

In 2016, Prine was named winner of the PEN/Song Lyrics Award, given to two songwriters every other year by the PENNew England chapter. Prine also released For Better, or Worse, a follow-up to In Spite of Ourselves. The album features country music covers spotlighting some of the most prominent female voices in the genre, including; Alison Krauss, Kacey Musgraves, and Lee Ann Womack, as well as Iris DeMent, the only guest artist to appear on both compilation albums

On February 8, 2018, Prine announced his first new album of original material in 13 years, titled The Tree of Forgiveness. The album features guest artists Jason Isbell, Amanda Shires, Dan Auerbach, and Brandi Carlile. Alongside the announcement, Prine released the track “Summer’s End”. The album became Prine’s highest-charting album on the Billboard 200.

In 2019, he recorded several tracks including “Please Let Me Go ‘Round Again”—a song which warmly confronts the end of life—with longtime friend and compatriot Swamp Dogg in his final recording session.

Most of today’s music doesn’t even have any melody, they’re based on beats. And pop numbers are cotton candy, they could be written by school kids, they’ve got no depth, despite the industry hyping them. And then there’s someone like John Prine. Who was always about the songs, who never wavered, who grew by being small, by nailing the experience of the average person, struggling to get by, at least emotionally, if not monetarily. And isn’t it funny how Prine’s music survives. Will it be heard forty or fifty years from now? I don’t know, but the odds are greater than those of the songs on the hit parade.

Prine never sold out, he was the genuine article. And he might not have been in the mainstream, but he was always in the landscape. He even survived cancer. He seemed unkillable. And now he’s gone.

Prine underwent cancer surgery on his throat in 2008 – and on his lungs in 2013 – but joked that it had actually improved his singing voice. Grammy-winning singer/songwriter John Prine died on March, 2020, aged 73, due to Covid-19 complications.

Tributes:

Throughout his five-decade career, Prine was often labeled the “songwriter’s songwriter,” not just because his only chart-toppers were scored by other great writers recording his music, but because few songwriters were as universally beloved, admired, and envied by their peers as Prine was.

• Speaking to the Huffington Post in 2009, Dylan – who performed with Prine – described his music as “pure Proustian existentialism”.

• “Midwestern mind trips to the nth degree. And he writes beautiful songs.”

• Robbie Robertson, from The Band – who used to back Dylan – described Prine as “a genius”.

• “His work… a beacon of clear white light cutting through the dark days,” added former Led Zeppelin frontman and solo star Robert Plant. “His charm, humour and irony we shall miss greatly.”

• He won his first of four Grammy Awards in 1991, for The Missing Years, which bagged best contemporary folk album. It was a category he would top again in 2005 for Fair and Square.

“We join the world in mourning the passing of revered country and folk singer/songwriter John Prine,” the Recording Academy wrote in a statement.

• “Widely lauded as one of the most influential songwriters of his generation, John’s impact will continue to inspire musicians for years to come. We send our deepest condolences to his loved ones.”

• “If I can make myself laugh about something I should be crying about, that’s pretty good,” he said.

• “If God’s got a favorite songwriter, I think it’s John Prine,” Kristofferson said at Prine’s 2003 Nashville Songwriter’s Hall of Fame induction.

• “He’s just one of the greats, and an old, old soul,” his friend Rosanne Cash once said of him. Roger Waters declared in 2008 that he prefers the “extra-ordinarily eloquent music” of Prine to the modern bands influenced by Pink Floyd’s work, like Radiohead. Prine’s music, the Floyd bassist/vocalist said, lives on the same plane as icons like John Lennon and Neil Young.

• And the reigning American bard-in-chief Bob Dylan was effusive in one 2009 interview, naming Prine as among his favorite writers, adding: “Prine’s stuff is pure Proustian existentialism. Midwestern mindtrips to the nth degree. And he writes beautiful songs… Nobody but Prine could write like that.”

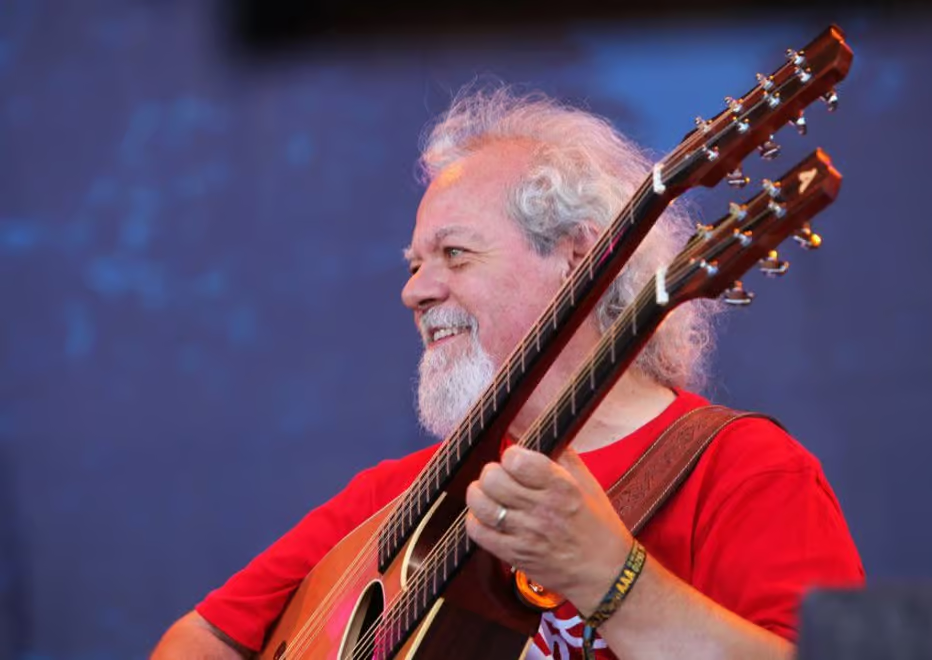

October 26, 2019 – Paul Barrere was born on July 3, 1948, the son of Hollywood actors Paul Bryar and Claudia Bryar. He joined celebrated cult band Little Feat in 1973, before the band recorded their third full-length LP, the gold-certified ‘Dixie Chicken’. For the recording of its fourth album, Feats Don’t Fail Me Now (1974), he wrote the title track. As Barrere stayed with the group, he took, along with keyboard player Bill Payne, an increasing role in singing, playing, and writing, as bandleader/founder

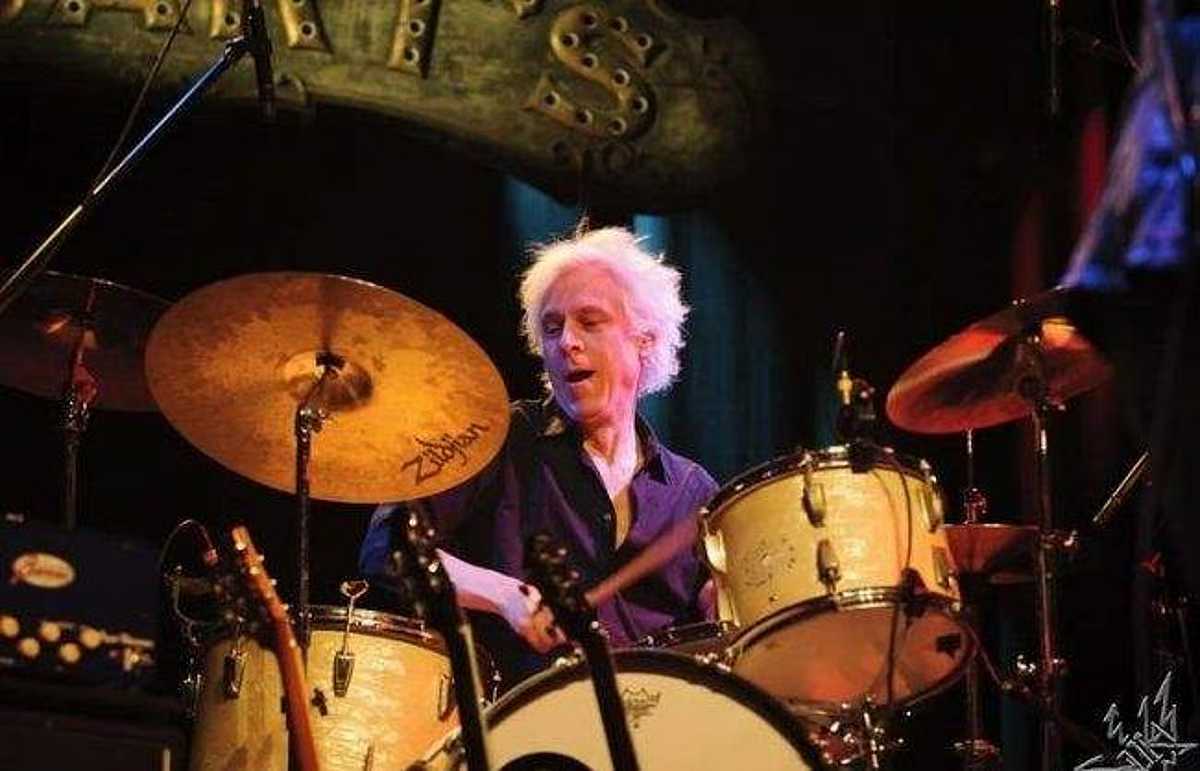

October 26, 2019 – Paul Barrere was born on July 3, 1948, the son of Hollywood actors Paul Bryar and Claudia Bryar. He joined celebrated cult band Little Feat in 1973, before the band recorded their third full-length LP, the gold-certified ‘Dixie Chicken’. For the recording of its fourth album, Feats Don’t Fail Me Now (1974), he wrote the title track. As Barrere stayed with the group, he took, along with keyboard player Bill Payne, an increasing role in singing, playing, and writing, as bandleader/founder  Peter ‘Ginger’ Baker – Cream/Blind Faith – was born on 19 August 1939 in Lewisham, South London. His mother, Ruby May worked in a tobacco shop. His father, Frederick Louvain Formidable Baker, was a bricklayer employed by his own father, who owned a construction business and was a lance corporal in the Royal Corps of Signals in World War II; he died in the 1943 Dodecanese campaign. Baker went to Pope Street School, where he was considered “one of the better players” in the football team, and then to Shooter’s Hill Grammar School. Here he was nicknamed “Ginger” for his shock of flaming red hair.

Peter ‘Ginger’ Baker – Cream/Blind Faith – was born on 19 August 1939 in Lewisham, South London. His mother, Ruby May worked in a tobacco shop. His father, Frederick Louvain Formidable Baker, was a bricklayer employed by his own father, who owned a construction business and was a lance corporal in the Royal Corps of Signals in World War II; he died in the 1943 Dodecanese campaign. Baker went to Pope Street School, where he was considered “one of the better players” in the football team, and then to Shooter’s Hill Grammar School. Here he was nicknamed “Ginger” for his shock of flaming red hair. Eddie Money was born Edward Joseph Mahoney in Manhattan, New York City on March 21, 1949, to a large family of Irish Catholic descent. His parents were Dorothy Elizabeth (née Keller), a homemaker, and Daniel Patrick Mahoney, a police officer. He grew up in Levittown, New York, but spent some teenage years in Woodhaven, Queens, New York City. Money was a street singer from the age of eleven. As a teenager, he played in rock bands, in part to get dates from cheerleaders. He was thrown out of one high school for forging a report card. In 1967, he graduated from Island Trees High School.

Eddie Money was born Edward Joseph Mahoney in Manhattan, New York City on March 21, 1949, to a large family of Irish Catholic descent. His parents were Dorothy Elizabeth (née Keller), a homemaker, and Daniel Patrick Mahoney, a police officer. He grew up in Levittown, New York, but spent some teenage years in Woodhaven, Queens, New York City. Money was a street singer from the age of eleven. As a teenager, he played in rock bands, in part to get dates from cheerleaders. He was thrown out of one high school for forging a report card. In 1967, he graduated from Island Trees High School. Robert Hunter (78) – the Grateful Dead – was born on June 23, 1941 in Arroyo Grande CA. Hunter’s father was an alcoholic, who deserted the family when Hunter was seven, according to Grateful Dead chronicler Dennis McNally. Hunter spent the next few years in foster homes before returning to live with his mother. These experiences drove him to seek refuge in books, and he wrote a 50-page fairy tale before he was 11. His mother married again, to Norman Hunter, whose last name Robert took. The elder Hunter was a publisher, who gave Robert lessons in writing. Hunter attended high school in Palo Alto, learning to play several instruments as a teenager. His family moved to Connecticut, where he attended the

Robert Hunter (78) – the Grateful Dead – was born on June 23, 1941 in Arroyo Grande CA. Hunter’s father was an alcoholic, who deserted the family when Hunter was seven, according to Grateful Dead chronicler Dennis McNally. Hunter spent the next few years in foster homes before returning to live with his mother. These experiences drove him to seek refuge in books, and he wrote a 50-page fairy tale before he was 11. His mother married again, to Norman Hunter, whose last name Robert took. The elder Hunter was a publisher, who gave Robert lessons in writing. Hunter attended high school in Palo Alto, learning to play several instruments as a teenager. His family moved to Connecticut, where he attended the

July 22, 2019 – Art Neville was born on 17 December 1937 the oldest son in the famous New Orleans blues/funk family that created the Neville Bothers. Art was born in New Orleans to Arthur Neville and his wife, Amelia (nee Landry). His father was a station porter fond of singing tunes by Nat King Cole and the Texan bluesman Charles Brown. His mother was part of a dance act with her brother, George “Big Chief Jolly” Landry.

July 22, 2019 – Art Neville was born on 17 December 1937 the oldest son in the famous New Orleans blues/funk family that created the Neville Bothers. Art was born in New Orleans to Arthur Neville and his wife, Amelia (nee Landry). His father was a station porter fond of singing tunes by Nat King Cole and the Texan bluesman Charles Brown. His mother was part of a dance act with her brother, George “Big Chief Jolly” Landry. June 6, 2019 – Dr. John was born Malcolm John Rebennack in New Orleans on November 20, 1941, and early on got the nickname “Mac.”

June 6, 2019 – Dr. John was born Malcolm John Rebennack in New Orleans on November 20, 1941, and early on got the nickname “Mac.”

March 17, 2019 – Bernie Tormé (guitarist for Ozzy, Gillan, Dee Snider and others) was born in Dublin on March 18, 1952, where he learned to play guitar. In 1974 he moved to London, joining bassist John McCoy in heavy rockers Scrapyard. After forming the Bernie Tormé Band two years later, he re-joined McCoy as a member of former Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan’s new solo project, playing on four Gillan albums: Mr. Universe, Glory Road, Future Shock and Double Trouble.

March 17, 2019 – Bernie Tormé (guitarist for Ozzy, Gillan, Dee Snider and others) was born in Dublin on March 18, 1952, where he learned to play guitar. In 1974 he moved to London, joining bassist John McCoy in heavy rockers Scrapyard. After forming the Bernie Tormé Band two years later, he re-joined McCoy as a member of former Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan’s new solo project, playing on four Gillan albums: Mr. Universe, Glory Road, Future Shock and Double Trouble.

March 22, 2019 – Scott Walker (the Walker Brothers) was born January 9, 1943 in Hamilton, Ohio, despite the fact that he was perceived as British. One of the more enigmatic figures in rock history, Scott Walker was known as Scotty Engel when he cut obscure flop records in the late ’50s and early ’60s in the teen idol vein.

March 22, 2019 – Scott Walker (the Walker Brothers) was born January 9, 1943 in Hamilton, Ohio, despite the fact that he was perceived as British. One of the more enigmatic figures in rock history, Scott Walker was known as Scotty Engel when he cut obscure flop records in the late ’50s and early ’60s in the teen idol vein. March 16, 2019 – Dick Dale was born Richard Monsour in Boston on May 4, 1937 1937; his father was Lebanese, his mother Polish. As a child, he was exposed to folk music from both cultures, which had an impact on his sense of melody and the ways string instruments could be picked. He also heard lots of big band swing, and found his first musical hero in drummer Gene Krupa, who later wound up influencing a percussive approach to guitar so intense that Dale regularly broke the heaviest-gauge strings available and ground his picks down to nothing several times in the same song.

March 16, 2019 – Dick Dale was born Richard Monsour in Boston on May 4, 1937 1937; his father was Lebanese, his mother Polish. As a child, he was exposed to folk music from both cultures, which had an impact on his sense of melody and the ways string instruments could be picked. He also heard lots of big band swing, and found his first musical hero in drummer Gene Krupa, who later wound up influencing a percussive approach to guitar so intense that Dale regularly broke the heaviest-gauge strings available and ground his picks down to nothing several times in the same song.

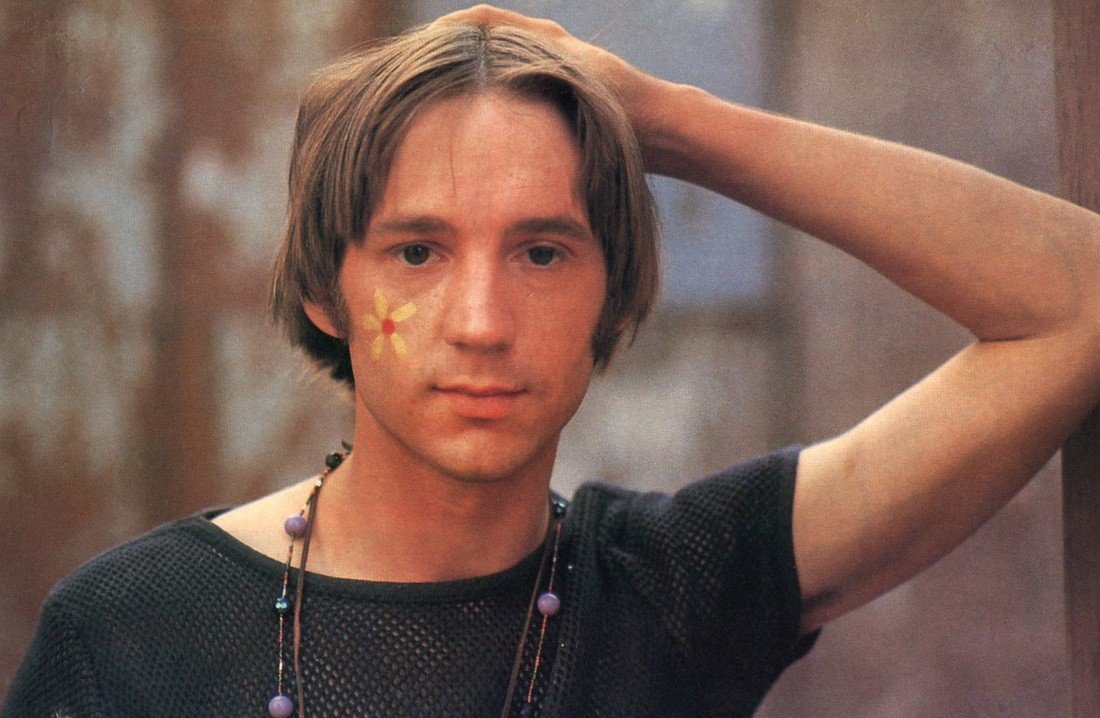

Peter Tork (The Monkees) was born Peter Halsten Thorkelson on February 13, 1942 in Washington DC. His father John taught economics at the University of Connecticut. He began studying piano at the age of nine, showing an aptitude for music by learning to play several different instruments, including the banjo, French horn and both acoustic bass and guitars. Tork attended Windham High School in Willimantic, Connecticut, and was a member of the first graduating class at E. O. Smith High School in Storrs, Connecticut. He attended Carleton College in Minnesota but, after flunking out, moved to New York City, where he became part of the folk music scene in Greenwich Village and with his guitar and five-string banjo he began playing small folk clubs. He billed himself as Tork, a nickname handed down by his father, and reportedly played with members of the soon-to-be formed band Lovin’ Spoonful (Summer in the City). While there, he befriended other up-and-coming musicians such as Stephen Stills (Crosby, Stills Nash and Young).When Tork “failed to break open the folk circuit,” as he later phrased it, he moved to Long Beach, California in mid-1965. Later that summer, he fielded two calls from his friend Stephen Stills (Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young), who had auditioned with more than 400 others for the Monkees. Stills urged Tork to try out. “They told Steve, ‘Your hair and teeth aren’t photogenic, but do you know anyone who looks like you that can sing?’ And Steve told them about me,” Tork told the Washington Post in 1983.

Peter Tork (The Monkees) was born Peter Halsten Thorkelson on February 13, 1942 in Washington DC. His father John taught economics at the University of Connecticut. He began studying piano at the age of nine, showing an aptitude for music by learning to play several different instruments, including the banjo, French horn and both acoustic bass and guitars. Tork attended Windham High School in Willimantic, Connecticut, and was a member of the first graduating class at E. O. Smith High School in Storrs, Connecticut. He attended Carleton College in Minnesota but, after flunking out, moved to New York City, where he became part of the folk music scene in Greenwich Village and with his guitar and five-string banjo he began playing small folk clubs. He billed himself as Tork, a nickname handed down by his father, and reportedly played with members of the soon-to-be formed band Lovin’ Spoonful (Summer in the City). While there, he befriended other up-and-coming musicians such as Stephen Stills (Crosby, Stills Nash and Young).When Tork “failed to break open the folk circuit,” as he later phrased it, he moved to Long Beach, California in mid-1965. Later that summer, he fielded two calls from his friend Stephen Stills (Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young), who had auditioned with more than 400 others for the Monkees. Stills urged Tork to try out. “They told Steve, ‘Your hair and teeth aren’t photogenic, but do you know anyone who looks like you that can sing?’ And Steve told them about me,” Tork told the Washington Post in 1983. November 3, 2018 – Glenn Schwartz (the James Gang) was born on March 20, 1940 in Cleveland Ohio. While in Los Angeles on tour with the James Gang in 1967, Schwartz strolled onto the infamous Sunset Strip and stopped next to a small group of people listening to street preacher Arthur Blessitt, according to Stevenson’s book. Some time later he professed conversion to Christianity, saying “I was finally blessed by mercy for I heard the Gospel of Christ.”

November 3, 2018 – Glenn Schwartz (the James Gang) was born on March 20, 1940 in Cleveland Ohio. While in Los Angeles on tour with the James Gang in 1967, Schwartz strolled onto the infamous Sunset Strip and stopped next to a small group of people listening to street preacher Arthur Blessitt, according to Stevenson’s book. Some time later he professed conversion to Christianity, saying “I was finally blessed by mercy for I heard the Gospel of Christ.” Tony Joe White – October 24, 2018 was born on July 23, 1943, in Oak Grove, Louisiana as the youngest of seven children who grew up on a cotton farm. He first began performing music at school dances, and after graduating from high school he performed in night clubs in Texas and Louisiana.

Tony Joe White – October 24, 2018 was born on July 23, 1943, in Oak Grove, Louisiana as the youngest of seven children who grew up on a cotton farm. He first began performing music at school dances, and after graduating from high school he performed in night clubs in Texas and Louisiana.

Otis Rush was born near Philadelphia, Mississippi on April 29, 1934 during the Great Depression, the son of sharecroppers Julia Campbell Boyd and Otis C. Rush. He was one of seven children and worked on the farm throughout his childhood. His mother regularly took him out of school so that he could add to the family income when the cotton was high and white landowners wanted extra labor.

Otis Rush was born near Philadelphia, Mississippi on April 29, 1934 during the Great Depression, the son of sharecroppers Julia Campbell Boyd and Otis C. Rush. He was one of seven children and worked on the farm throughout his childhood. His mother regularly took him out of school so that he could add to the family income when the cotton was high and white landowners wanted extra labor. Maarten Allcock (61) – multi instrumentalist with Fairport Convention and Jethro Tull,

Maarten Allcock (61) – multi instrumentalist with Fairport Convention and Jethro Tull,

Ed King, ( Lynyrd Skynyrd/Strawberry Alarm Clock) – September 14, 1949 – August 22, 2018 was born in Glendale California and a guitar prodigy from early on in his life. Not even 18 years old, he became a founding member of the Los Angeles band Strawberry Alarm Clock, remembered for their 1967 #1 single “Incense and Peppermints.”

Ed King, ( Lynyrd Skynyrd/Strawberry Alarm Clock) – September 14, 1949 – August 22, 2018 was born in Glendale California and a guitar prodigy from early on in his life. Not even 18 years old, he became a founding member of the Los Angeles band Strawberry Alarm Clock, remembered for their 1967 #1 single “Incense and Peppermints.”

January 15, 2018 – Dolores O’Riordan (The Cranberries) was born Dolores Mary Eileen O’Riordan on September 6, 1971 brought up in Ballybricken, a town in County Limerick, Ireland. She was the daughter of Terence and Eileen O’Riordan and the youngest of seven children. She attended Laurel Hill Coláiste FCJ school in Limerick.

January 15, 2018 – Dolores O’Riordan (The Cranberries) was born Dolores Mary Eileen O’Riordan on September 6, 1971 brought up in Ballybricken, a town in County Limerick, Ireland. She was the daughter of Terence and Eileen O’Riordan and the youngest of seven children. She attended Laurel Hill Coláiste FCJ school in Limerick.

December 12, 2017 – Pat DiNizio (The Smithereens) was born October 12, 1955 in Scotch Plains, New Jersey, where he actually lived his entire life. As a youngster, he was inspired by the pop music emanating from his transistor radio in the ‘60s and the hit tunes being written by his musical idols Buddy Holly, The Beatles, and The Beau Brummels among others.

December 12, 2017 – Pat DiNizio (The Smithereens) was born October 12, 1955 in Scotch Plains, New Jersey, where he actually lived his entire life. As a youngster, he was inspired by the pop music emanating from his transistor radio in the ‘60s and the hit tunes being written by his musical idols Buddy Holly, The Beatles, and The Beau Brummels among others.

November 22, 2017 – Tommy Keene was born on June 30, 1958 in Evanston, Illinois and raised and graduated from Walter Johnson High School in Bethesda, Maryland (class of 1976), (which was also the alma mater of fellow musician Nils Lofgren). Keene played drums in one version of Lofgren’s early bands but moved to guitar later when he attended the University of Maryland.

November 22, 2017 – Tommy Keene was born on June 30, 1958 in Evanston, Illinois and raised and graduated from Walter Johnson High School in Bethesda, Maryland (class of 1976), (which was also the alma mater of fellow musician Nils Lofgren). Keene played drums in one version of Lofgren’s early bands but moved to guitar later when he attended the University of Maryland.

November 21, 2017 – Wayne Cochran (The CC Riders) was born Talvin Wayne Cochran near Macon, Georgia, and grew up in roughly the same environs his idol James Brown and friend Otis Redding had, be it on the other side of the tracks.

November 21, 2017 – Wayne Cochran (The CC Riders) was born Talvin Wayne Cochran near Macon, Georgia, and grew up in roughly the same environs his idol James Brown and friend Otis Redding had, be it on the other side of the tracks.

November 9, 2017 – Hans Vermeulen (Sandy Coast) was born on September 18, 1947 in Voorburg, the Hague in the Netherlands. He grew up in what was to become the birthplace of Nederpop, which produced bands like Golden earring (Radar Love) and Shocking Blue (Venus), Q 65, Rob Hoeke and many others.

November 9, 2017 – Hans Vermeulen (Sandy Coast) was born on September 18, 1947 in Voorburg, the Hague in the Netherlands. He grew up in what was to become the birthplace of Nederpop, which produced bands like Golden earring (Radar Love) and Shocking Blue (Venus), Q 65, Rob Hoeke and many others. November 7, 2017 – Paul Buckmaster born on June 13, 1946 in London England.

November 7, 2017 – Paul Buckmaster born on June 13, 1946 in London England.

October 7, 2017 – Jimmy Beaumont (The Skyliners) was born on October 21, 1940 in the Knoxville neighborhood of Pittsburgh, PA. While in his teens he formed the bebop group the Crescents. Joe Rock, a promo man working with Beaumont’s group, one day jotted down the lyrics to a song as he sat in his car at a series of stoplights, lamenting that his girlfriend was leaving for flight attendant school on the West Coast.

October 7, 2017 – Jimmy Beaumont (The Skyliners) was born on October 21, 1940 in the Knoxville neighborhood of Pittsburgh, PA. While in his teens he formed the bebop group the Crescents. Joe Rock, a promo man working with Beaumont’s group, one day jotted down the lyrics to a song as he sat in his car at a series of stoplights, lamenting that his girlfriend was leaving for flight attendant school on the West Coast.

September 5, 2017 – Rick Stevens (Tower of Power) was born Donald Stevenson on February 23, 1941 in Port Arthur, Texas, but didn’t stay there long, as a few years later his parents moved to Reno, Nevada. Rick first sang in public at the tender age of four, when his family set him up on a chair in front of the congregation at their church.

September 5, 2017 – Rick Stevens (Tower of Power) was born Donald Stevenson on February 23, 1941 in Port Arthur, Texas, but didn’t stay there long, as a few years later his parents moved to Reno, Nevada. Rick first sang in public at the tender age of four, when his family set him up on a chair in front of the congregation at their church. September 5, 2017 – Holger Czukay was born on March 24, 1938 in the Free City of Danzig (since 1945 Gdańsk, Poland), from which his family was expelled after World War II. Due to the turmoil of the war, Czukay’s primary education was limited. One pivotal early experience, however, was working, when still a teenager, at a radio repair-shop, where he became fond of the aural qualities of radio broadcasts (anticipating his use of shortwave radio broadcasts as musical elements) and became familiar with the rudiments of electrical repair and engineering.

September 5, 2017 – Holger Czukay was born on March 24, 1938 in the Free City of Danzig (since 1945 Gdańsk, Poland), from which his family was expelled after World War II. Due to the turmoil of the war, Czukay’s primary education was limited. One pivotal early experience, however, was working, when still a teenager, at a radio repair-shop, where he became fond of the aural qualities of radio broadcasts (anticipating his use of shortwave radio broadcasts as musical elements) and became familiar with the rudiments of electrical repair and engineering.

September 3, 2017 – Dave Hlubek was born on August 28, 1951 in Jacksonville, Florida. At the age of 5 or 6, Hlubek and his family moved to the naval base in Oahu, Hawaii, where he attended Waikiki Elementary School. From there, Hlubek’s father was transferred and the family moved to Sunnyvale, California, then to Mountain View, and finally settling in San Jose. It was the South Bay that Dave called home during the next few years, before moving back to Jacksonville, Florida, around 1965. There he attended and graduated from Forrest High School.

September 3, 2017 – Dave Hlubek was born on August 28, 1951 in Jacksonville, Florida. At the age of 5 or 6, Hlubek and his family moved to the naval base in Oahu, Hawaii, where he attended Waikiki Elementary School. From there, Hlubek’s father was transferred and the family moved to Sunnyvale, California, then to Mountain View, and finally settling in San Jose. It was the South Bay that Dave called home during the next few years, before moving back to Jacksonville, Florida, around 1965. There he attended and graduated from Forrest High School. September 3, 2017 – Walter Becker (Steely Dan) was born February 20, 1950 in Queens, New York. Becker was raised by his father and grandmother, after his parents separated when he was a young boy and his mother, who was British, moved back to England. They lived in Queens and as of the age of five in Scarsdale, New York. Becker’s father sold paper-cutting machinery for a company which had offices in Manhattan.

September 3, 2017 – Walter Becker (Steely Dan) was born February 20, 1950 in Queens, New York. Becker was raised by his father and grandmother, after his parents separated when he was a young boy and his mother, who was British, moved back to England. They lived in Queens and as of the age of five in Scarsdale, New York. Becker’s father sold paper-cutting machinery for a company which had offices in Manhattan.

July 21, 2017 – Kenny Shields was born in 1947 in the farming community of Nokomis, Saskatchewan, Canada. His passion for music and entertaining emerged at the age of six when he entered and won an amateur talent show. While continuing his interest in music and singing, upon graduation from secondary school he moved to Saskatoon to attend university but was immediately recruited by the city’s premiere band – Witness Incorporated.

July 21, 2017 – Kenny Shields was born in 1947 in the farming community of Nokomis, Saskatchewan, Canada. His passion for music and entertaining emerged at the age of six when he entered and won an amateur talent show. While continuing his interest in music and singing, upon graduation from secondary school he moved to Saskatoon to attend university but was immediately recruited by the city’s premiere band – Witness Incorporated.

July 13, 2017 – Simon Holmes (The Hummingbirds) was born on March 28, 1963 in the southern beachside suburb of Melbourne, Australia. The family lived in Bentleigh, before shifting to Turramurra in 1967, before going overseas for three years, in upstate New York, where Holmes started school at Myers Corner. The family then moved to Geneva, Switzerland. He spent part of his childhood in Canberra, attending the AME School: an alternative education institution and then Hawker College. Holmes moved to Sydney in the early 1980s. He started studying anthropology and archaeology at the University of Sydney, but left after two years.

July 13, 2017 – Simon Holmes (The Hummingbirds) was born on March 28, 1963 in the southern beachside suburb of Melbourne, Australia. The family lived in Bentleigh, before shifting to Turramurra in 1967, before going overseas for three years, in upstate New York, where Holmes started school at Myers Corner. The family then moved to Geneva, Switzerland. He spent part of his childhood in Canberra, attending the AME School: an alternative education institution and then Hawker College. Holmes moved to Sydney in the early 1980s. He started studying anthropology and archaeology at the University of Sydney, but left after two years.

You must be logged in to post a comment.