Sinéad O’Connor (56) was born on 8 December 1966 in Dublin, Ireland at the Cascia House Nursing Home on Baggot Street in Dublin. She was named Sinéad after Sinéad de Valera, the mother of the doctor who presided over her delivery (Éamon de Valera, Jnr.), and Bernadette in honor of Saint Bernadette of Lourdes. She was the third of five children; an older brother is the novelist Joseph O’Connor.

Sinéad O’Connor (56) was born on 8 December 1966 in Dublin, Ireland at the Cascia House Nursing Home on Baggot Street in Dublin. She was named Sinéad after Sinéad de Valera, the mother of the doctor who presided over her delivery (Éamon de Valera, Jnr.), and Bernadette in honor of Saint Bernadette of Lourdes. She was the third of five children; an older brother is the novelist Joseph O’Connor.

Her parents were John Oliver “Seán” O’Connor, a structural engineer later turned barrister and chairperson of the Divorce Action Group and Johanna Marie O’Grady (1939–1985). She attended Dominican College Sion Hill school in Blackrock, County Dublin. Abused by an obsessively religious mother during her childhood, growing up in a politically charged environment of the Irish clashes and terrorist actions, she created a willingness to take a stand that made her powerful — and threatening, at the same time. Her mother also taught her to steal from the collection plate at Mass and from charity tins. In 1979, at age 13, O’Connor went to live with her father, who had recently returned to Ireland after re-marrying in the United States, in 1976.

At the age of 15, following her acts of shoplifting and truancy, O’Connor was placed for 18 months in a Magdalene asylum, the Grianán Training Centre in Drumcondra, which was run by the Order of Our Lady of Charity. She thrived in certain aspects, particularly in the development of her writing and music, but she chafed under the imposed conformity of the asylum, despite being given freedoms not granted to the other girls, such as attending an outside school and being allowed to listen to music, write songs, etc. For punishment, O’Connor described how “if you were bad, they sent you upstairs to sleep in the old folks’ home. You’re in there in the pitch black, you can smell the shit and the puke and everything, and these old women are moaning in their sleep … I have never—and probably will never—experience such panic and terror and agony over anything.”

One of the volunteers at the Grianán centre was the sister of Paul Byrne, drummer for the band In Tua Nua, who heard O’Connor singing “Evergreen” by Barbra Streisand. She recorded a song with them called “Take My Hand” but they felt that at 15, she was too young to join the band. Through an ad she placed in Hot Press in mid-1984, she met Colm Farrelly. Together they recruited a few other members and formed a band named Ton Ton Macoute, the Haitian mythological bogeyman, Tonton Macoute (“Uncle Gunnysack”), who kidnaps and punishes unruly children by snaring them in a gunny sack (macoute) before carrying them off to be consumed for breakfast. The band moved to Waterford briefly while O’Connor attended Newtown School, but she soon dropped out of school and followed them to Dublin, where their performances received positive reviews. Their sound was inspired by Farrelly’s interest in world music, though most observers thought O’Connor’s singing and stage presence were the band’s strongest features.

O’Connor’s time with Ton Ton Macoute brought her to the attention of the music industry, and she was eventually signed by Ensign Records. She also acquired an experienced manager, Fachtna Ó Ceallaigh, former head of U2‘s Mother Records. Soon after she was signed, she embarked on her first major assignment, providing the vocals for the song “Heroine”, which she co-wrote with the U2 guitarist the Edge for the soundtrack to the film Captive. Ó Ceallaigh, who had been fired by U2 for complaining about them in an interview, was outspoken with his views on music and politics, and O’Connor adopted the same habits.

With Fachtna Ó Ceallaigh as her manager, O’Connor made her recorded debut with “Heroine,” a song she wrote and performed with the Edge that appeared on the soundtrack to the film Captive. While working on her debut album, she scrapped the initial tapes on the grounds that the production was too Celtic. Taking over the production duties herself, she re-recorded the album with a sound that emphasized her alternative rock and hip-hop influences. The result was November 1987’s The Lion and the Cobra, one of the year’s most acclaimed debut records. The album performed strongly throughout the world, reaching number 27 on the U.K. Albums chart, number 36 on the Billboard 200 Albums chart in the U.S., and charting in several other countries. The Lion and the Cobra was certified gold in the U.K., U.S., and Netherlands; in Canada, it was certified platinum. It spawned the hits “Mandinka,” “Troy,” and “I Want Your (Hands on Me),” and O’Connor’s accolades included a Grammy nomination for Best Female Rock Vocal Performance. While promoting the album, she had another brush with controversy when she defended the actions of the provisional IRA (she later retracted these comments).

Following The Lion and the Cobra’s success, O’Connor appeared on The The’s 1989 album Mind Bomb and made her film debut in that year’s Hush-a-Bye-Baby, for which she also wrote the music. But she delivered a harrowing masterpiece with her next album, March 1990’s I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got. Sparked by the dissolution of her marriage to drummer John Reynolds, the album was boosted by the global chart-topping single and video “Nothing Compares 2 U” (originally penned by Prince in 1984 for one of his side projects) and established her as a major star. Reaching number one in eighteen countries, the album went double platinum in the U.S. and U.K., quintuple platinum in Canada, and platinum in six other nations.

In her memoire Sinéad had a few choice words to say about Prince: Prince had composed the song in 1984, deciding to give it to the Family, a side project featuring the singers Susannah Melvoin and Paul Peterson. But the track never gained much recognition when the band released its self-titled album in 1985.

The response was considerably different when O’Connor, working with the Japanese jazz musician Gota Yashiki and the producer Nellee Hooper, recorded a stripped-down version for her 1990 album “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got.”

“Nothing Compares 2 U” became a No. 1 hit in 17 countries, topped the Billboard Hot 100 for four straight weeks and helped win O’Connor a Grammy (which she later refused to accept). The track’s popular music video, featuring a close-up of O’Connor’s shaved head and piercing gaze, was itself nominated for a Grammy.

“As far as I’m concerned, it’s my song,” O’Connor told The New York Times in 2021.

Prince was pleased to see O’Connor’s version become so popular, Melvoin said in an interview this week.

“When it hit and it was doing remarkably well, he had a big smile on his face about it.” Melvoin said. “He loved it. At one point later in his life, he was known to say, ‘Thank you for all the beautiful houses, Sinead.’”

Peterson said he was so shocked when he first heard O’Connor’s cover over the car radio that he had to pull over.

“I didn’t know who she was, and I felt like I had ownership in that song even though I didn’t write it,” he said in an interview. “So I think I was a little disappointed that our version didn’t get out there at the incredible rate that hers did.”

At the same time, Peterson said, he feels thrilled that O’Connor’s cover has been so influential. “It’s incredible the amount of people’s lives that song has touched,” he said. “I was just thrilled to be a small part of that.”

Melvoin said Prince wrote the song both about herself and his housekeeper, Sandy Scipioni, who left the role after her father died. Melvoin and Prince had been intimately involved for years, she said, but were encountering difficulties in their relationship when he wrote “Nothing Compares 2 U.”

It took only a short time for Prince to draft the song at his Eden Prairie warehouse studio, Susan Rogers, Prince’s sound engineer, said in Duane Tudahl’s book “Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions.”

“I was amazed how beautiful it was,” Rogers told Tudahl. “He took his notebook and he went off to the bedroom, wrote the lyrics very quickly, came back out and sang it.”

O’Connor wrote in her memoir, “Rememberings,” that she felt a particular resonance with the lines, “All the flowers that you planted Mama/In the backyard/All died when you went away.”

“Every time I perform it, I feel it’s the only time I get to spend with my mother and that I’m talking with her again,” wrote O’Connor, who was 18 when her mother died in a car crash. “There’s a belief that she’s there, that she can hear me and I can connect to her.”

Although “Nothing Compares 2 U” was vital to O’Connor’s career, she grew conflicted about Prince, writing in her memoir about a distressing encounter at his Los Angeles residence.

They had first met at a club around the time of O’Connor’s debut album in 1987, she wrote, but did not interact again until after her version of “Nothing Compares 2 U” became a hit in America.

When O’Connor arrived at Prince’s residence, she wrote, the singer criticized her for swearing in interviews. Prince then suggested the two engage in a pillow fight, she wrote, and began hitting her with a pillowcase containing a pillow and some hard object.

O’Connor fled and Prince pursued her in his car, she wrote, until she escaped to a nearby home. (A spokeswoman for Prince’s estate did not respond to requests for comment.)

“I never wanted to see that devil again,” O’Connor wrote.

Though I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got was nominated for four Grammy Awards and won the award for Best Alternative Music Performance, Sinead O’Connor refused to accept them; similarly, she did not attend the Brit Awards ceremony when she won the award for International Female Solo Artist. Later in 1990, she performed in Roger Waters’ Berlin performance of The Wall and appeared on the Red Hot Organization’s AIDS fundraising and Cole Porter tribute album Red Hot + Blue: A Tribute to Cole Porter with a cover of “You Do Something to Me.”

O’Connor became the target of derision in the US for refusing to perform in New Jersey if “The Star Spangled Banner” was played prior to her appearance, a move that brought public criticism from no less than mob asshole Frank Sinatra. She also made headlines for pulling out of an appearance on the NBC program Saturday Night Live in response to the misogynist persona of guest host Andrew Dice Clay.

O’Connor continued to defy expectations with her third album, September 1992’s Am I Not Your Girl?. A collection of mid-20th century pop standards and torch songs that sparked her desire to be a singer when she was young, its radically different sound and style led to mixed reviews and produced only a fraction of the commercial success she had with I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got. Nevertheless, the album was a Top Ten hit in the U.K. and achieved gold status there and in three other European countries. O’Connor followed the album’s release with her most controversial action yet: She ended her October 1992 performance on Saturday Night Live by ripping up a photo of Pope John Paul II to protest the sexual abuse of children in the Catholic Church. The resulting condemnation was unlike any she’d previously encountered. Two weeks after the SNL performance, she was booed off the stage at a Bob Dylan tribute concert at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

Kris Kristofferson comforted Sinéad when she was booed off the stage at this concert.

Sinéad O’Connor, just 25 years old at the time.

He later wrote this for her. May we all have her courage. May we all tell the truth.

—-

“I’m singing this song for my sister Sinéad

Concerning the god awful mess that she made

When she told them her truth just as hard as she could

Her message profoundly was misunderstood

There’s humans entrusted with guarding our gold

And humans in charge of the saving of souls

And humans responded all over the world

Condemning that bald headed brave little girl

And maybe she’s crazy and maybe she ain’t

But so was Picasso and so were the saints

And she’s never been partial to shackles or chains

She’s too old for breaking and too young to tame

It’s askin’ for trouble to stick out your neck

In terms of a target a big silhouette

But some candles flicker and some candles fade

And some burn as true as my sister Sinéad

And maybe she’s crazy and maybe she ain’t

But so was Picasso and so were the saints

And she’s never been partial to shackles or chains

She’s too old for breaking and too young to tame

In the wake of the controversy, O’Connor stepped back from the public eye. For several months, she studied bel canto singing at Dublin’s Parnell School of Music, then joined Peter Gabriel’s Secret World tour in 1993 (she also contributed vocals to Gabriel’s 1992 album Us). That year, her song “You Made Me the Thief of Your Heart” appeared on the soundtrack to the film In the Name of the Father. Inspired by her bel canto lessons, O’Connor took a confessional approach on her next album, September 1994’s Universal Mother. A stripped-down set of songs featuring the single “Fire on Babylon” and a cover of Nirvana’s “All Apologies,” it reached number 19 in the U.K. and number 36 in the U.S., and was certified gold in the U.K., Austria, and Canada. The videos for “Fire on Babylon” and “Famine” were nominated for the Best Short Form Music Video Grammy Award. Also in 1994, O’Connor appeared in A Celebration: The Music of Pete Townshend and The Who, a pair of Carnegie Hall concerts produced by Roger Daltrey to celebrate his fiftieth birthday. The following year, she appeared on the Lollapalooza bill, and in 1996 she sang on Pink Floyd’s Richard Wright’s album Broken China. A year later, she played the Virgin Mary in Neil Jordan’s film The Butcher Boy and issued The Gospel Oak EP, a tender collection of songs about motherhood. O’Connor teamed up with the Red Hot Organization once more for 1998’s Red Hot + Rhapsody: The Gershwin Groove, on which she performed “Someone to Watch Over Me.”

After moving to Atlantic Records, she delivered her first full-length release in six years with June 2000’s Faith and Courage album. Tackling themes of survival and catharsis, the album featured collaborators including Wyclef Jean and Brian Eno. Charting throughout Europe and reaching number 55 in the U.S., Faith and Courage earned O’Connor some of her strongest reviews in some time. For her next album, October 2002’s Sean-Nós Nua, she reinterpreted traditional Irish songs in her own style. Along with reaching number three on the Irish charts, the album peaked at number one on the Top World Albums chart in the U.S. Health issues led O’Connor to take a break from intensive recording and performing for a few years. During this time, she covered Dolly Parton’s “Dagger Through the Heart” on the 2003 tribute album Just Because I’m a Woman: The Songs of Dolly Parton, appeared on Massive Attack’s 100th Window, and issued She Who Dwells in the Secret Place of the Most High Shall Abide Under the Shadow of the Almighty, a compilation of demos, unreleased tracks, and a late 2002 Dublin concert. Collaborations followed in 2005, gathering appearances on other artists’ records throughout her long career.

Sinéad O’Connor returned in October 2005 with Throw Down Your Arms, a collection of classic reggae songs from the likes of Burning Spear, Peter Tosh, and Bob Marley. Recorded at Kingston, Jamaica’s Tuff Gong and Anchor Studios with Sly & Robbie and released on O’Connor’s own That’s Why There’s Chocolate and Vanilla imprint, the album reached the number four spot on Billboard’s Top Reggae Albums chart. In 2006, she returned to the studio to begin work on her next album. Inspired by the complexities of the world post-9/11, June 2007’s double album Theology featured covers of spiritually minded songs as well as originals given acoustic and full-band interpretations. The album appeared on the charts of several European countries and reached number 15 on the Independent Albums chart in both the U.K. and the U.S. That year, O’Connor also lent her vocals to Ian Brown’s anti-war single “Illegal Attacks” as well as another song on his album The World Is Yours. In 2010, she collaborated with Mary J. Blige on a version of the Gospel Oak song “This Is to Mother You.” Produced by A Tribe Called Quest’s Ali Shaheed Muhammad, the song’s proceeds were donated to Girls Educational and Mentoring Services (GEMS). Two years later, O’Connor earned a Golden Globe nomination for Best Original Song for “Lay Your Head Down,” which appeared on the soundtrack to the film Albert Nobbs.

O’Connor’s ninth album, How About I Be Me (And You Be You)?, appeared in February 2012, offering raw yet often optimistic songs about sexuality, religion, hope, and despair that were seen as a return to form by some critics. The album was one of her more popular later releases, appearing on the charts of many European countries, reaching number 33 in the U.K., and number 115 in the U.S. A limited edition of How About I Be Me (And You Be You)? included excerpts of shows in Dublin, London, and Reykjavík. Her next album, August 2014’s I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss, took inspiration from Lean In’s female empowerment campaign “Ban Bossy. As heard on the lead single “Take Me to the Church,” the album was a rock-oriented and melodious affair. Building on How About I Be Me (And You Be You)?’s popularity, I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss topped the Irish charts, peaked at number 22 in the U.K. and at number 83 in the U.S. That November, O’Connor took part in Band Aid 30’s updated version of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?,” which raised funds to combat the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa.

In September 2019, O’Connor closed out the 2010s with her first live performance in five years, singing “Nothing Compares 2 U” with the Irish Chamber Orchestra on Irish radio. The following October, she issued a cover of Mahalia Jackson’s “Trouble of the World” to raise money for Black Lives Matter charities. Her 2021 memoir, Rememberings, was acclaimed as one of the year’s best books and praised for its wit and candor. The following year, a feature length documentary about her life and career, Nothing Compares, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival; it was named Best Feature Documentary at the 2023 Irish Film & Television Awards. Though O’Connor was working on a new album, her grief over the death of her son Shane in 2022 led her to cancel its release and her upcoming performances. After she released a version of the traditional tune “The Skye Boat Song” in February 2023, Irish broadcaster RTE honored O’Connor by giving I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got the inaugural award for Classic Irish Album at the RTE Choice Music Awards, which she dedicated to the Irish refugee community.

In July 2023, O’Connor, who a couple of months earlier had retreated to her London apartment to step away from the loneliness, died some time around July 25 at age 56. She still died alone!

This stunningly beautiful woman Sinéad O’Connor once said she’d cut her hair off in response to male record executives who’d been trying to goad her into wearing miniskirts, into appearing more traditionally feminine. She’d grown up believing that it was treacherous to be a woman, she said. To be recognized as beautiful was only ever a liability: “I always had that sense that it was quite important to protect myself, make myself as unattractive as I possibly could.”

It is thoroughly sad that in this country called America, Sinéad O’Connor is still better known a the woman who tore up a picture of the Pope to defy how the Catholic Church approached the tragedy of child abuse, than for hurtingly beautiful songs as “Nothing Compares to You” or “Sacrifice”. Just unbelievable!

America was never ready to meet Sinéad O’Connor

February 22, 1989, the 31st annual Grammy Awards. Among the nominees for Best Rock Vocal Performance, Female are Tina Turner, Pat Benatar, Melissa Etheridge, Toni Childs, and Sinéad O’Connor. O’Connor has performed once on Late Night with David Letterman, but she has yet to appear on primetime American television. Tuxedo-clad host Billy Crystal introduces her to the tens of millions watching at home, explaining that O’Connor is a 21-year-old singer from Ireland and that “with her very first album, The Lion and the Cobra, she has served notice that this is no ordinary talent.”

Most people point to O’Connor’s destruction of a photo of Pope John Paul II, during her October 1992 performance on Saturday Night Live, as the reason for her exile from the pop world. But it was on this night in Los Angeles, three years prior, that revealed from the outset what the rest of the rest of the world would learn soon enough: her willingness to take a stand made her powerful — and threatening.

As the first few notes of O’Connor’s runaway college radio hit “Mandinka” kick in, the curtain rises on a darkened stage. She steps forward as if entering from a void, her hair shorn nearly to the scalp, her midriff exposed by a black halter top, her baggy, low-slung blue jeans ripped and torn. She touches her face almost like she can’t believe she’s there. O’Connor’s voice is clear and cutting, alternating between a whisper and a dare. If you look closely you might notice that she is wearing an infant’s sleepsuit tied behind her waist as she rocks back and forth in her Doc Martens, wailing, “I don’t know no shame/I feel no pain/I can’t see the flame!” Even from a distance, you can’t miss the massive man in the crosshairs of a gun that’s been painted onto the side of her shaved head, an arresting image even if you don’t immediately catch the reference.

After she was done, reporters from the L.A. Times described O’Connor as looking nervous backstage. Although they commended her performance, and her outfit, they quoted her remarking on what had just transpired, as though she were crashing the party. “I thought it was a little odd that they asked me to perform, because of the way I look,” she told them, “But I find it encouraging that they asked, because it’s an acknowledgment that they are prepared not to be so safe about the music and push forward with people slightly off the wall.”

If only that were true. ”Mandinka” was a fearless battle cry, but it was only her opening act. The onesie O’Connor wore was her son Jake’s, a middle finger to the executives at her record label who had warned her that motherhood and a career were incompatible. The man in the crosshairs was Public Enemy’s logo, which Chuck D described as symbolizing the Black man in America. She wore it as a badge of solidarity with the band, and by extension, all rappers who had been erased from the program. For years, the powerful white men who controlled the Recording Academy had dismissed rap as a passing fad or considered it dangerously subversive. Yet by 1989 the genre had become too popular to simply ignore. So they decided to confer the first-ever award for Best Rap Performance, but not to televise it. The trophy went to DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince for their G-rated pop crossover single “Parents Just Don’t Understand,” but they weren’t on hand that night, having led a boycott that also included fellow nominees Salt-N-Pepa and LL Cool J.

O’Connor was in fact no ordinary talent, and she had served notice, using music’s biggest night to put herself on the map and set the terms of her agenda. Despite not winning the Grammy, she subverted the record label’s hot-girl marketing strategy at a time when starlets like Tiffany and Debbie Gibson were burning up the pop charts. Despite the Recording Academy’s attempts to suppress rap, she managed to foil those plans too. O’Connor showed us a fierceness that made her great, but also foreshadowed how it would all come crashing down, sooner rather than later.

Kathryn Ferguson’s new documentary Nothing Compares, now in theaters and streaming on Showtime, traces that arc, starting with O’Connor’s early life in theocratic Ireland, where she suffered severe abuse at the hands of her devoutly religious mother, then became a rebellious teen who found her voice at a Catholic girls reformatory school. After signing her first recording contract at 18, and concluding that the producer assigned to mold her debut was zapping the life out of her songs, O’Connor took over the reins herself, pouring all of her intensity into The Lion and the Cobra. But her record company still tried to soften her appearance, switching out the photo on the album cover because the original would make her look too “angry” to American audiences.

Despite being decidedly anti-pop, her piercing musical memoir became a surprise commercial hit, ultimately going gold. O’Connor then topped that with her multi-platinum follow up, 1990’s I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got. Thanks in large part to non-stop MTV airplay of the music video for the Prince-penned lead single “Nothing Compares 2 U,” O’Connor became a global celebrity, her expressive face a meme before memes. But as her star rose even higher, so did the scrutiny. When O’Connor withdrew from a 1990 appearance on SNL after learning that the comedian Andrew Dice Clay was scheduled to host, The Diceman, known for his misogynistic and homophobic routines, performed a skit poking fun at the “bald chick.” After O’Connor declined to have the national anthem played before a show at New Jersey’s Garden State Arts Center, Frank Sinatra said she must be “one stupid broad” and threatened to “kick her ass.”

Politicians organized protests against O’Connor. DJs refused to play her records. O’Connor was widely accused of censorship when it was she who was being censored. She was also criticized for being “anti-American” and ungrateful for the success she had achieved. Still, that fall she swept the MTV Video Music Awards with wins for Best Female Music Video and Best Post-Modern Music Video, and even bested Madonna for Video of the Year.

O’Connor seemed a little shocked. Aside from saying thanks when she was presented with the first two trophies, she said almost nothing. But with the third, she doubled down, using her speech to connect her experience with the industry’s censorship of Black artists. Explaining her reasons for not wanting the national anthem played before her shows, O’Connor told the global audience, “It’s the American system I have disrespect for, which imposes censorship on people, which as far as I’m concerned is racism.” O’Connor then dug in even deeper. Referencing rap trio 2 Live Crew’s recent banning in Florida on obscenity grounds, she called attention to how MTV also used “obscenity” as an excuse not to play rap videos, stating that “censorship in any form is bad, but when it’s racism disguised as censorship, it’s even worse.”

When the Grammys came around again a few months later, O’Connor was nominated in four categories, but by then she’d had enough of the pop life, and the silence and complicity it demanded. She refused to attend the 1991 awards ceremony or accept her eventual win for Best Alternative Music Performance. Ahead of the event, O’Connor wrote an open letter to the Recording Academy in which she criticized the music industry for promoting false and materialistic values rather than rewarding artistic merit.

Photo: Recording Academy/GRAMMYs/YouTube

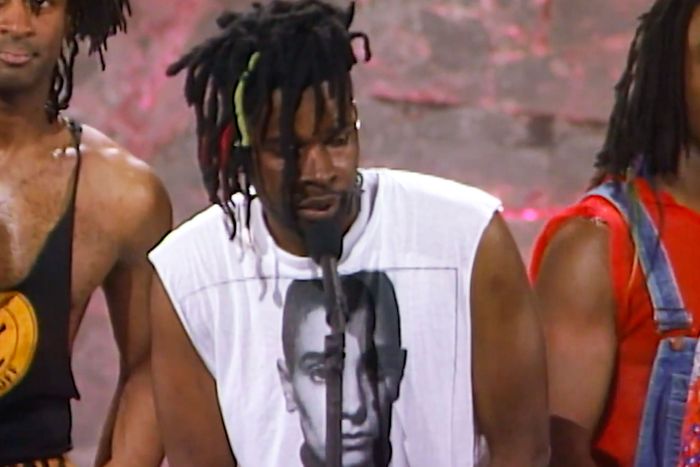

The award presentation for Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group was still not to be televised, so when nominee Public Enemy learned of O’Connor’s letter, the band decided to boycott too, making its own statement and returning the solidarity she had offered in ‘89. When Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid accepted his Grammy that night for Best Hard Rock Performance, he appeared onstage with a giant photo of O’Connor on his T-shirt. When reporters asked Reid about it, he re-centered the conversation on representation, reminding them that the Recording Academy doesn’t dictate his dress code.

Hindsight has shown us that O’Connor was right to call out the music industry’s commercialism, and its racial and gender bias, as early as 1989 — issues that the Grammys are only beginning to seriously grapple with in the face of waning influence and relevance. Rather than asking about whether her decision to speak out was self-sabotage, better questions would be: What kinds of sacrifices would O’Connor have had to make to sustain her status as a pop star? What kinds of sacrifices have we made not to see or hear what she was trying to tell us?

Sinéad O’Connor, you were the original truth sayer who wouldn’t go easy into the night. The original “difficult” woman who didn’t make it easy. Because easy wasn’t the right thing to do and it wasn’t the truth. Gone too soon. “Nothing compares to you.”